Battle of Lepanto

| Battle of Lepanto | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War and the Ottoman-Habsburg wars | |||||||

The Battle of Lepanto, H. Letter, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich/London. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

208 ships

22,840 soldiers |

251 ships

31,490 soldiers |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,500 dead 17 ships lost[2] |

20,000 dead, wounded or captured[2][3] 137 ships captured 50 ships sunk 10,000 Christian galley slaves freed |

||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Lepanto took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Spain (including its territories of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia), the Republic of Venice, the Papacy, the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Savoy, the Knights Hospitaller and others, decisively defeated the main fleet of the Ottoman Empire.

The five-hour battle was fought at the northern edge of the Gulf of Patras, off western Greece, where the Ottoman forces sailing westwards from their naval station in Lepanto (Turkish: İnebahtı; Greek: Ναύπακτος, Naupaktos or Έπαχτος, Épahtos) met the Holy League forces, which had come from Messina.[4] Victory gave the Holy League temporary control over the Mediterranean, protected Rome from invasion, and prevented the Ottomans from advancing further into Europe. Lepanto was the last major naval battle fought almost entirely between oar-powered galleys, and has been assigned great symbolic importance since then.

Contents |

Forces

- See Battle of Lepanto order of battle for a detailed list of ships and commanders involved in the battle.

The Holy League's fleet consisted of 206 galleys and 6 galleasses (large new galleys, invented by the Venetians, which carried substantial artillery) and was ably commanded by Don Juan de Austria, the illegitimate son of Emperor Charles V and half brother of King Philip II of Spain. Vessels had been contributed by the various Christian states: 109 galleys and 6 galleasses from the Republic of Venice, 80 galleys from Spain, 12 Tuscan galleys of the Order of Saint Stephen, 3 galleys each from Genoa, Malta, and Savoy, and some privately owned galleys. All members of the alliance viewed the Turkish navy as a significant threat, both to the security of maritime trade in the Mediterranean Sea and to the security of continental Europe itself. Notwithstanding, Spain preferred to preserve its galleys for its own wars against the nearby sultanates of the Barbary Coast rather than expend its naval strength for Venetian benefit, although it contributed the bulk of the Christian infantry.[5] The various Christian contingents met the main force, that of Venice (under Venier), in July and August 1571 at Messina, Sicily. Don Juan de Austria arrived on the 23rd of August.

This fleet of the Christian alliance was manned by 12,920 sailors. In addition, it carried almost 28,000 fighting troops: 10,000 Spanish regular infantry of excellent quality,[5] 7,000 Germans and Croatians[6] in Spanish pay, 6,000 Italian mercenaries, and 5,000 Venetian soldiers. Also, Venetian oarsmen were mainly free citizens and were able to bear arms adding to the fighting power of their ship, whereas convicts were used to row many of the galleys in other Holy League squadrons. Many of the galleys in the Turkish fleet were also rowed by slaves, often Christians who had been captured in previous conquests and engagements.[7] Free oarsmen were generally acknowledged to be superior by all combatants, but were gradually replaced in all galley fleets (including those of Venice from 1549) during the 16th century by cheaper slaves, convicts and prisoners-of-war owing to rapidly rising costs.[8]

The Ottoman galleys were manned by 13,000 experienced sailors—generally drawn from the maritime nations of the Ottoman Empire, namely Berbers, Greeks, Syrians, and Egyptians—and 34,000 soldiers.[9] Ali Pasha (Turkish: "Kaptan-ı Derya Ali Paşa"), supported by the corsairs Chulouk Bey of Alexandria and Uluj Ali (Uluç Ali), commanded an Ottoman force of 222 war galleys, 56 galliots, and some smaller vessels. The Turks had skilled and experienced crews of sailors but were significantly deficient in their elite corps of Janissaries.

An important and arguably decisive advantage for the Christians was their numerical superiority in guns and cannons aboard their ships, and probably the better fighting quality of the Spanish infantry.[5] It is estimated the Christians had 1,815 guns, while the Turks had only 750 with insufficient ammunition.[1][3] The Christians embarked with their much improved arquebusier and musketeer forces, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bowmen.[10]

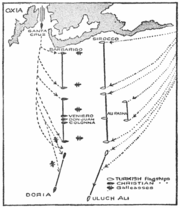

Deployment

The Christian fleet formed up in four divisions in a North-South line. At the northern end, closest to the coast, was the Left Division of 53 galleys, mainly Venetian, led by Agostino Barbarigo, with Marco Querini and Antonio da Canale in support. The Centre Division consisted of 62 galleys under Don Juan de Austria himself in his Real, along with Sebastiano Venier, later Doge of Venice, Mathurin Romegas and Marcantonio Colonna. The Right Division to the south consisted of another 53 galleys under the Genoese Giovanni Andrea Doria, great-nephew of the famous Andrea Doria. Two galleasses, which had side-mounted cannon, were positioned in front of each main division, for the purpose, according to Miguel de Cervantes (who served on the galley Marquesa during the battle), of preventing the Turks from sneaking in small boats and sapping, sabotaging or boarding the Christian vessels. A Reserve Division was stationed behind (that is, to the west of) the main fleet, to lend support wherever it might be needed. This reserve division consisted of 38 galleys - 30 behind the Centre Division commanded by Álvaro de Bazán, and four behind each wing. A scouting group was formed, from two Right Wing and six Reserve Division galleys. As the Christian fleet was slowly turning around Point Scropha, Doria's Right Division, at the off-shore side, was delayed at the start of the battle and the Right's galleasses did not get into position.

The Turkish fleet consisted of 57 galleys and 2 galliots on its Right under Chulouk Bey, 61 galleys and 32 galliots in the Centre under Ali Pasha in the Sultana, and about 63 galleys and 30 galliots in the South off-shore under Uluj Ali. A small reserve existed of 8 galleys, 22 galliots and 64 fustas, behind the Centre body. Ali Pasha is supposed to have told his Christian galley-slaves: "If I win the battle, I promise you your liberty. If the day is yours, then God has given it to you." Don Juan, more laconically, warned his crew: "There is no paradise for cowards."[11]

The battle

The Left and Centre galleasses had been towed half a mile ahead of the Christian line. When the battle started, the Turks mistook the Galeasses to be merchant supply vessels and set out to attack them. This proved to be disastrous, the galeasses, with their many guns, alone were said to have sunk up to 70 Turkish galleys, before the Turkish fleet left them behind. Their attacks also disrupted the Ottoman formations. As the battle started, Doria found that Uluj Ali's galleys extended further to the south than his own, and so headed south to avoid being out-flanked, instead of holding the Christian line. After the battle Doria was accused of having maneuvered his fleet away from the bulk of the battle to avoid taking damage and casualties. Regardless, he ended up being out maneuvered by Uluj Ali, who turned back and attacked the southern end of the Centre Division, taking advantage of the big gap that Doria had left.

In the north, Chulouk Bey had managed to get between the shore and the Christian North Division, with six galleys in an outflanking move, and initially the Christian fleet suffered. Commander Barbarigo was killed by an arrow, but the Venetians, turning to face the threat, held their line. The return of a galleass saved the Christian North Division. The Christian Centre also held the line with the help of the Reserve, after taking a great deal of damage, and caused great damage to the Muslim Centre. In the south, off-shore side, Doria was engaged in a melee with Uluj Ali's ships, taking the worse part. Meanwhile Uluj Ali himself commanded 16 galleys in a fast attack on the Christian Centre, taking six galleys - amongst them the Maltese Capitana, killing all but three men on board. Its commander, Pietro Giustiniani, Prior of the Order of St. John, was severely wounded by five arrows, but was found alive in his cabin. The intervention of the Spaniards Álvaro de Bazán and Juan de Cardona with the reserve turned the battle, both in the Centre and in Doria's South Wing.

Uluj Ali was forced to flee with 16 galleys and 24 galliots, abandoning all but one of his captures. During the course of the battle, the Ottoman Commander's ship was boarded and the Spanish tercios from 3 galleys and the Turkish Janissaries from seven galleys fought on the deck of the Sultana[12]. Twice the Spanish were repelled with heavy casualties, but at the third attempt, with reinforcements from Álvaro de Bazán's galley, they took the ship. Müezzinzade Ali Pasha was killed and beheaded, against the wishes of Don Juan. However, when his severed head was displayed on a pike from the Spanish flagship, it contributed greatly to the destruction of Turkish morale. Even after the battle had clearly turned against the Turks, groups of Janissaries still kept fighting with all they had. It is said that at some point the Janissaries ran out of weapons and started throwing oranges and lemons at their Christian adversaries, leading to awkward scenes of laughter among the general misery of battle.[3]

The battle concluded around 4 pm. The Turkish fleet suffered the loss of about 210 ships—of which 117 galleys, 10 galliots and three fustas were captured and in good enough condition for the Christians to keep. On the Christian side 20 galleys were destroyed and 30 were damaged so seriously that they had to be scuttled. One Venetian galley was the only prize kept by the Turks; all others were abandoned by them and recaptured.

Uluj Ali, who had captured the flagship of the Maltese Knights, succeeded in extricating most of his ships from the battle when defeat was certain. Although he had cut the tow on the Maltese flagship in order to get away, he sailed to Constantinople, gathering up other Ottoman ships along the way and finally arriving there with 87 vessels. He presented the huge Maltese flag to Sultan Selim II who thereupon bestowed upon him the honorary title of "kιlιç" (Sword); Uluj thus became known as Kılıç Ali Pasha.

The Holy League had suffered around 7,500 soldiers, sailors and rowers dead, but freed about as many Christian prisoners. Turkish casualties were around 15,000, and at least 3,500 were captured.

Aftermath

The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. The defeat was mourned as an act of Divine Will, contemporary chronicles recording that "the Imperial fleet encountered the fleet of the wretched infidels and the will of God turned another way." [13] To half of Christendom, this event encouraged hope for the downfall of the Turk, who was regarded as the "Sempiternal Enemy of the Christian". Indeed, the Empire lost all but 30 of its ships and as many as 30,000 men,[10] and some Western historians have held it to be the most decisive naval battle anywhere on the globe since the Battle of Actium of 31 BC. However, shortly after the defeat, Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, suggested to the Venetian emissary Marcantonio Barbaro that the Christian triumph at Lepanto was meaningless, saying:

You come to see how we bear our misfortune. But I would have you know the difference between your loss and ours. In wresting Cyprus from you, we deprived you of an arm; in defeating our fleet, you have only shaved our beard. An arm when cut off cannot grow again; but a shorn beard will grow all the better for the razor.[14]

Indeed, despite the significant victory, the Holy League's disunity prevented the victors from capitalizing on their triumph. Plans to seize the Dardanelles, as a step towards recovering Constantinople for Christendom, were ruined by bickering amongst the allies. With a massive effort, the Ottoman Empire rebuilt its navy and imitated the successful Venetian galeasses. By 1572, more than 150 galleys and 8 galleasses had been built, adding eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean.[15] Within six months a new fleet of 250 ships (including 8 galleasses) was able to reassert Ottoman naval supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean.[16] On 7 March 1573 the Venetians thus recognized by treaty the Ottoman possession of Cyprus, which had fallen to the Turks under Piyale Pasha on 3 August 1571, just two months before Lepanto, and remained Turkish for the next three centuries, and that summer the Ottoman navy ravaged the geographically vulnerable coasts of Sicily and southern Italy. However, while the ships were relatively easily replaced,[10] it proved much harder to man them, since so many experienced sailors, oarsmen and soldiers had been lost. The loss of so many of its experienced sailors at Lepanto sapped the fighting effectiveness of the Ottoman navy, a fact emphasized by their avoidance of major confrontations with Christian navies in the years following the battle. Especially critical was the loss of most of the caliphate's composite bowmen, which, far beyond ship rams and early firearms, were the Ottoman's main embarked weapon. Historian John Keegan notes that the losses in this highly specialised class of warrior were irreplaceable in a generation, and in fact represented "the death of a living tradition" for the Ottomans.[10] Historian Paul K. Davis has argued that:

"This Turkish defeat stopped Turkey's expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten."[17]

.jpg)

In the 1574 Capture of Tunis, the Ottomans retook the strategic city of Tunis from the Spanish supported Hafsid dynasty, that had been re-installed when Don Juan's forces reconquered the city from the Ottomans the year before. With the long-standing Franco-Ottoman alliance coming into play they were able to resume naval activity in the western Mediterranean. In 1579 the capture of Fez completed Ottoman conquests in Morocco that had begun under Süleyman the Magnificent. The establishment of Ottoman suzerainty over the area placed the entire coast of the Mediterranean from the Straits of Gibraltar to Greece (with the exceptions of the Spanish controlled trading city of Oran and strategic settlements such as Melilla and Ceuta) – under Ottoman authority.

Thus, this victory for the Holy League was historically important not only because the Turks lost 80 ships sunk and 130 captured by the Allies, and 30,000 men killed (not including 12,000 Christian galley slaves who were freed) while allied losses were only 7,500 men and 17 galleys - but because the victory heralded the end of Turkish supremacy in the Mediterranean.[10][18] It has been said that "after Lepanto the pendulum swung back the other way and the wealth began to flow from East to West", as well as "a crucial turning point in the ongoing conflict between the Middle East and Europe, which has not yet completely been resolved."[19]

Religious significance

The Holy League credited the victory to the Virgin Mary, whose intercession with God they had implored for victory through the use of the Rosary. Andrea Doria had kept a copy of the miraculous image of our Our Lady of Guadalupe given to him by King Philip II of Spain in his ship's state room.[20] Pope Pius V instituted a new Catholic feast day of Our Lady of Victory to commemorate the battle, which is now celebrated by the Catholic Church as the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary.[21][22]

Depictions in art and culture

The significance of Lepanto has inspired artists in various fields.

The only known commemorative music composed after the victory is the motet Canticum Moysis (Song of Moses Exodus 15) Pro victoria navali contra Turcas by the Spanish composer based in Rome Fernando de las Infantas[23]

There are many pictorial representations of the battle, including two in the Doge's Palace in Venice: by Paolo Veronese (above) in the Sala del Collegio and by Andrea Vicentino on the walls of the Sala dello Scrutinio, which replaced Tintoretto's Victory of Lepanto, destroyed by fire in 1577. Titian's Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto, using the battle as a background, hangs in the Prado in Madrid. The picture at the top of this article is the work of an unknown artist.

The Spanish poet Fernando de Herrera wrote the poem "Canción en alabanza de la divina majestad por la victoria del Señor Don Juan" in 1572.

The English author G. K. Chesterton wrote a poem Lepanto, first published in 1911 and republished many times since. It provides a series of poetic visions of the major characters in the battle, particularly the leader of the Christian forces, Don Juan of Austria (John of Austria). It closes with verses linking Miguel de Cervantes, who fought in the battle, with the "lean and foolish knight" he would later immortalize in Don Quixote.

The Italian author Emilio Salgari references the Battle of Lepanto in his novel Il Leone di Damasco published in 1910.

The American abstract painter Cy Twombly refers with 12 big pictures ('Lepanto', 2001) to the battle, one of his main works.

The Battle of Lepanto also inspired the name of a common anti-Turkey opening used by Italian and Austrian players in the board game Diplomacy. A successful Lepanto opening leaves Turkey effectively crippled and with almost no options left in the game. At the same time, a failed Lepanto can result in a serious loss of momentum for the allied forces.

The Battle of Lepanto is a scenario in Age of Empires II: The Conquerors.

See also

- Ottoman-Habsburg wars

- History of the Ottoman Navy

- List of Ottoman sieges and landings

- Barbary pirates

- Spanish Empire

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Miguel de Cervantes, called the manco de Lepanto (the one-armed from Lepanto) because he lost his arm during the fight.

- Battle of Naupactus (429 BC) fought at nearly the same location

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The number of Turkish guns is said to be deduced from list of booty after the battle. These lists are unlikely to be complete.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Confrontation at Lepanto by T.C.F. Hopkins, intro

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution, p. 88

- ↑ Luggis, Telemachus: "Sunday, 7 October 1571" pp. 19-23 Epsilon Istorica, Eleftherotypia, 9 November 2000. See also Chasiotis, Ioannis "The signing of 'Sacra Liga Antiturca' and the naval battle of Lepanto (7 October 1571)", Istoria tou Ellinikou Ethnous. Ekdotiki Athinon, vol. 10, Athens, 1974

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Stevens (1942), p. 61

- ↑ Clissold (1966), p. 43.

- ↑ John F. Guilmartin, Gunpowder and Galleys, p. 222-25

- ↑ The first regularly sanctioned use of convicts as oarsmen on Venetian galleys did not occur until 1549. re Tenenti, Cristoforo da Canal, pp. 83, 85. See Tenenti, Piracy and the Decline of Venice (Berkeley, 1967), pp. 124-25, for Cristoforo da Canal's comments on the tactical effectiveness of free oarsmen c. 1587 though he was mainly concerned with their higher cost. Ismail Uzuncarsili, Osmanli Devletenin Merkez ve Bahriye Teskilati (Ankara, 1948), p. 482, cites a squadron of 41 Ottoman galleys in 1556 of which the flagship and two others were rowed by Azabs, salaried volunteer light infantrymen, three were rowed by slaves, and the remaining 36 were rowed by salaried mercenary Greek oarsmen.

- ↑ Stevens (1942), p. 63

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 A History Of Warfare - Keegan, John, Vintage, 1993

- ↑ Stevens (1942), p. 64

- ↑ A flag taken at Lepanto by the Knights of the Order of Saint Stephen, and traditionally said to be the standard of the Turkish commander, is still in display, together with other Turkish flags, in the Church of the seat of the Order in Pisa. [1], [2] (in italian)

- ↑ Wheatcroft 2004, pp.33-34

- ↑ Wheatcroft 2004, p. 34

- ↑ J. Norwich, A History of Venice, 490

- ↑ L. Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire, 272

- ↑ Davis, Paul K. "100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present"

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ Serpil Atamaz Hazar, “Review of Confrontation at Lepanto: Christendom vs. Islam,” The Historian 70.1 (Spring 2008): 163.

- ↑ Badde, Paul. Maria von Guadalupe. Wie das Erscheinen der Jungfrau Weltgeschichte schrieb. ISBN 3548605613.

- ↑ Answers to Recent Questions

- ↑ EWTN on Battle of Lepanto (1571) [4]

- ↑ Stevenson, R. Chapter 'Other church masters' section 14. 'Infantas' in Spanish Cathedral Music in the Golden Age pp316-318.

References

- Anderson, R. C. Naval Wars in the Levant 1559-1853 (2006), ISBN 1-57898-538-2

- Beecher, Jack The Galleys at Lepanto Hutchinson, London, 1982; ISBN 0-09147-920-7

- Bicheno, Hugh. Crescent and Cross: The Battle of Lepanto 1571, pbk., Phoenix, London, 2004, ISBN 1-84212-753-5

- Capponi, Niccolò (2006). Victory of the West:The Great Christian-Muslim Clash at the Battle of Lepanto. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-30681-544-3.

- Chesterton, G. K. Lepanto with Explanatory Notes and Commentary, Dale Ahlquist, ed. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003). ISBN 1-58617-030-9

- Clissold, Von Stephen (1966). A short history of the Yugoslav peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-04676-9.

- Cakir, İbrahim Etem, "Lepanto War and Some Informatıon on the Reconstructıon of The Ottoman Fleet", Turkish Studies -International Periodical For The Language Literature and History of Turkish or Turkic, V o l u me 4 / 3 S p r i n g 2 0 0 9, pp. 512–531

- Cook, M.A. (ed.), "A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730", Cambridge University Press, 1976; ISBN 0-521-20891-2

- Currey, E. Hamilton, "Sea-Wolves of the Mediterranean", John Murrey, 1910

- Hanson, Victor D. Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power, Anchor Books, 2001. Published in the UK as Why the West has Won, Faber and Faber, 2001. ISBN 0-571-21640-4. Includes a chapter about the battle of Lepanto

- Hess, Andrew C. "The Battle of Lepanto and Its Place in Mediterranean History", Past and Present, No. 57. (Nov., 1972), pp. 53–73

- Stevens, William Oliver and Allan Westcott (1942). A History of Sea Power. Doubleday.

- Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, third revision by George Bruce, 1979

- Warner, Oliver Great Sea Battles (1968) has "Lepanto 1571" as its opening chapter. ISBN 0-89673-100-6

- The New Cambridge Modern History, Volume I - The Renaissance 1493-1520, edited by G. R. Potter, Cambridge University Press 1964

- Wheatcroft, Andrew (2004). Infidels: A History of the Conflict between Christendom and Islam. Penguin Books.

External links

- Battle of Lepanto animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

- "Lepanto cultural center*The Battle that Saved the Christian West

- Overview of the battle

- Lepanto: The Battle that Saved Christendom?

- "The Tactics of the Battle of Lepanto Clarified: The Impact of Social, Economic, and Political Factors on Sixteenth Century Galley Warfare"

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||